In the late evening of the 18th January I read the saddening news on Bluesky that Charles A. Doswell III has died in the age of 79 years. Doswell played an important role researching the basics of severe thunderstorms, supercell storms and tornadoes. I did not stand close to him and I had not have any contact or attended his talks or workshops in the last ten years. I did however take part in his one-day convective forecast workshop in October 2011, during the European Conference on Severe Storms (ECSS) in Palma de Mallorca. Doswell has been one of the old school guys who put much emphasis on haptic learning. We used large prints of surface weather charts to determine frontal systems or other boundaries to get a feeling for where convective weather could take place. Nothing like this was or is used anymore in European weather services, especially not at the private weather service where I was working at this time. Nevertheless I was taught the ingredients-based methodology going far beyond the index-based methodology which was sometimes overly present in this period. Doswell was the lead author with two other authorities in this area, Brooks and Maddox, of a famous paper about ingredients for flash floods (Doswell et al. 1996).

„The concept of ingredients-based forecasting is discussed as it might apply to a broader spectrum of forecast events than just flash flood forecasting.“

And it did! The concept has been extended to severe convective weather forecasting where it is now a standard forecasting procedure, at least for forecasters who excel their job wholeheartedly. Instead of relying only on cape, showalter, significant tornado parameter or other multiple-variable indices, he emphasized the overlap of moisture, instability and lift for deep moist convection, and wind shear for organized convection including mesocyclones.

Together with another colleague I tried to explain the new concept but it is always hard to get rid of tradition, even if it leads to frequent false prognosis. Some people rather clinged to precipitation forecasts only and where no precipitation was simulated, no convection could occur. But it was never such simple and sometimes no convection was triggered despite of model precipitation being present. Models weren’t such sophisticated ten years ago, and high resolution models had their difficulties with double penalty issues back then, still now despite major improvements. The US was also many steps ahead but the main reason for it may be that research, theory and practice are much more intertwined than in Europe, especially in german-speaking countries. In October 2012 I attended another Doswell workshop in Wiener Neustadt, eastern Austria. where we worked a whole week together. That’s where we also sat together an evening in the group of forecasters and got to know each other better. I remember I liked his blunt character just to say loud his opinion. In 2013 I guess I had a short e-mail exchange with his him where I complained about the fact my superiors disliked that I’ve done frequent case studies to verify our forecasts and to learn something for the future. I regulary stepped on the toes of long standing colleagues (and bosses) as I verified their forecasts too, which might have been embarassing at times. However I never intended to be promoted but I really want to improve myself. My superiors tried to shut me down – that’s when I started to look for another job. He said something very important:

„A weather service not verifying its own forecasts is untrustworthy.“

Verificiation is still the Achilles heel of many weather services and verification itself is often reduced to meeting key figures. I’m still convinced it is necessary to look beyond plain numbers and focus on the weathern pattern and if all ingredients were in place. It’s much more time-consuming to analyze weather patterns instead of simply running an program comparing operating figures. I’m glad I learned much about his way of thinking and it comes in handy every time I do a case study of a weather event. Many years ago I translated parts of his pet peeves into german. I especially liked his clarification about „air mass“ and „frontal thunderstorms“.

„Moreover, the development of thunderstorms is never random … they develop in particular places at particular times for reasons that we may not be able to observe and/or understand, but it is absurd to think that thunderstorms develop, in effect, for no reason!“

I try to teach this way of thinking until today, in my current webinar talks at the local Apenverein as well as in my job when I hear something like „storms develop out of the air mass today because no frontal boundary is present“. Then I try to look in detail about all possible trigger mechanisms including water vapour streamers (PV anomaly) before I make up my mind prematurely. In most cases something exists which can explain why thunderstorms seem to pop up randomly in a large area without a visible frontal bounday.

I also resent the term „convective temperatur“ (Auslösetemperatur) after I’ve read his pet peeves about it.

„What we really see is that deep convection usually commences as isolated convective clouds, perhaps at a few places along a line, usually well before the attainment of the „convective temperature“. Sometimes, however, the „convective temperature“ is reached and nothing happens. The implicit model associated with this term is that deep convection is initiated solely by elimination of the negative area through solar heating.„

In 2019 I hold a talk about outflow boundaries during a DWD forecasting workshop in Langen, Germany.

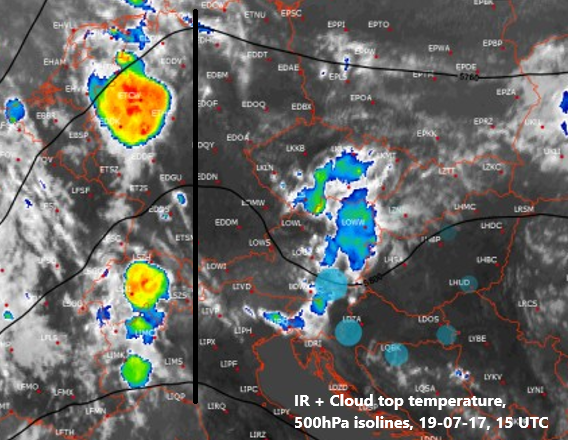

I presented a case in July 2017 when I had day shift at Salzburg airport. The convective temperature has been reached. Small cumulus clouds developed. A distinct outflow boundary propagated westward, triggered by deep moist convection far downstream over Danube area. However: Nothing happened with that outflow boundary. No deep moist convection developed! Why?

The answer lies in ingredients-based methodology! Instability and moisture aren’t sufficient to trigger deep moist convection alone. It is also necessary to have deep lift. The convection associated with the outflow boundary developed with an eastward moving trough over eastern Austria (visible in 500hPa isohypses) but the outflow boundary running westward entered an area with increasing subsidence due to an incoming upper-level ridge.

Six hours earlier, a bit upstream, a dry boundary layer has been present (inverted V profile), with modest CAPE values up to the tropopause. Dry upper levels indicated the increasing subsidence from the incoming ridge. This process further increased until the evening preventing deep moist convection at all. And that’s where I need Doswell’s conceptual model each time when I try find out the cause and effects of meteorological mysteries.

Therefore I’m thankful what I learned from him. Compared with a lot of other convective forecasters in that field, I only scratched at the surface. I’ve never been a stormchaser or got immersed into convective modelling but I’m curious and never fear to correct myself if new evidence turns up.

Farewell Chuck and thank you!